A petition launched on the UK parliament's own website calling for a special EU visa for hospitality has attracted more than 12,000 signatures in less than a week.

It’s difficult to know how many of those come from within the sector but its success illustrates the difficulty much of the industry currently has in hiring staff.

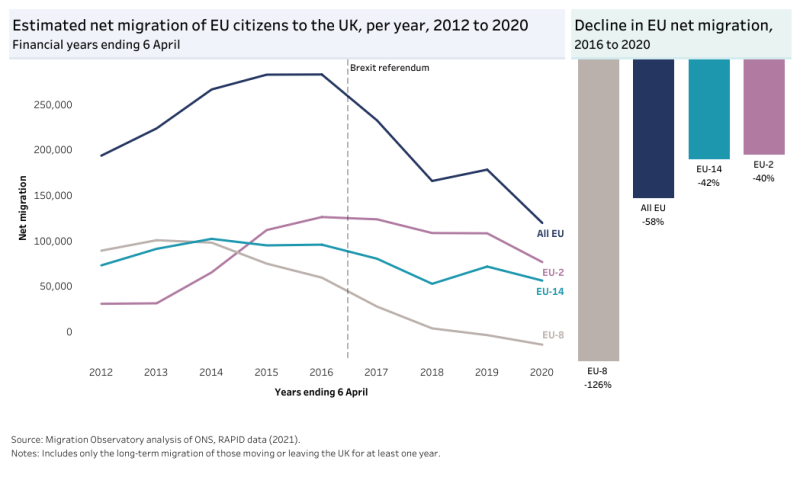

Of course the hospitality labour crisis is a global phenomenon, but a combination of factors has pushed the UK into an impossible position. Chief among those is the 2016 Brexit vote, which has removed freedom of movement resulting in a dramatic reduction in European immigration.

With unemployment still relatively low there are just not enough people to fill positions with industries like hospitality struggling to recruit.

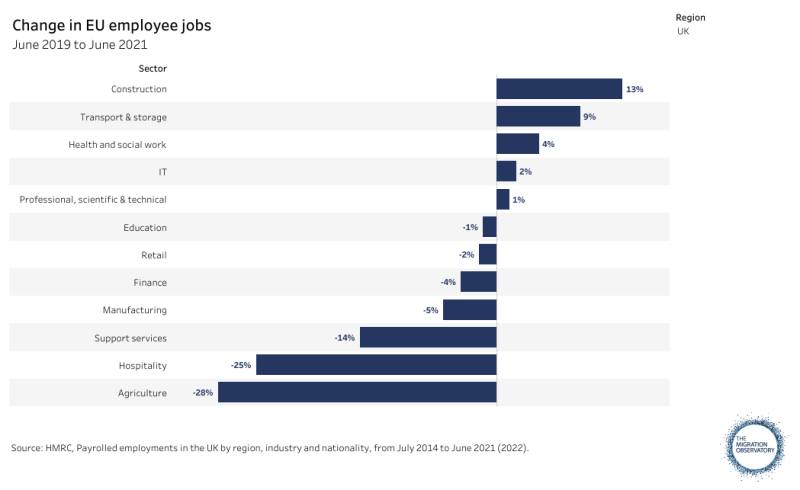

In a new report released earlier this month ReWAGE and the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford has shown that the end of free movement exacerbated recruitment issues faced by UK employers, although they acknowledged there were other factors as well including the pandemic, international sector-specific labour shortages, and an increase in early retirement.

According to the report entitled How is the End of Free Movement Affecting the Low-wage Labour Force in the UK?, the hospitality industry lost just over 98,000 EU citizen jobs in the two years to June 2021.

It’s difficult to see how things get any better as there are few easy solutions. The ideas often suggested are:

- Use technology to replace staff – possible in some areas but not in others

- Employ more UK staff – The industry has long talked about getting government help to encourage young people to join the sector.

- Lobby for sector-specific visas – Difficult to see this having any success with the anti-immigration Conservative Party in government

The idea of expanding visa eligibility for low-wage jobs is something the above report picks up on, specifically the Youth Mobility Scheme. This is currently largely restricted to 18 to 30-year-olds from a handful of countries (Australia, Canada, Monaco, New Zealand, San Marino and Iceland being the main ones). Adding EU countries would widen the pool considerably but would be politically difficult given the corner most political parties have backed themselves into.

Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, said: “While it is clear that ending free movement has made it harder for employers in low-wage industries to recruit staff, changing immigration policy to address shortages brings its own set of challenges. Low-wage work visa schemes are notoriously difficult to police and often open workers up to exploitation and abuse. It’s also surprisingly difficult to measure shortages and work out how to target immigration policy towards them.”

The inevitable decline of UK hospitality?

But what happens if technological solutions don’t make much of a difference, UK workers can’t be enticed to work in the sector and there is no change to visa policy? Well the report takes it to a logical conclusion for industries like hospitality.

"There is no consensus on whether shortages of workers in low-wage jobs are a problem and whether immigration policy should attempt to prevent them. Free movement from 2004 onwards facilitated the growth in some labour-intensive industries. As a result, the UK has larger labour-intensive industries—for example, higher production of soft fruit—than it is likely it would have done in the absence of free movement. However, there is no optimal size of each industry—and thus no reason to believe that the UK needs a hospitality or horticulture industry of a particular size. As noted above, the main long-run impact in the long term of restricting the growth in the low-wage labour force by ending free movement likely to be that the industry composition of the economy will be slightly different,” the report says.

The gist of this is that as a country, unless something changes, the types of jobs people do will change.

The authors go on to note: “The argument that the effects of free movement are small on average also masks different and potentially longer-lasting impacts in different locations. For example, sparsely populated areas that have relied on a thriving seasonal hospitality industry will not necessarily be able to replace that activity with something else if the hospitality industry declines. Hospitality makes up a higher share of businesses and of employment in some types of area, particularly villages, towns and cities located with wider areas that are sparsely populated. For example, in 2019/20, 14.6% of businesses in towns and cities located in sparsely populated regions in England were in hospitality, compared to 6.4% for England as a whole.”

This is a startling analysis and one without any easy solutions.